How the Niagara region made vital contributions to the 1969 moon landing

- Jeff Schober

- Jul 9, 2019

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 16, 2019

Local engineers and innovators were instrumental to the American space program

Fifty years ago this month, American astronauts touched down on the moon, and a new era of scientific achievement was realized across the planet. Until then, the idea of a person walking on the moon was the stuff of far-fetched science fiction novels.

People and companies around Buffalo made key contributions to the first lunar landing on July 20, 1969.

“The road to the moon went through Western New York,” said Walter Gordon, president of the Niagara Aerospace Museum in Niagara Falls. “This area was critical. If Western New York didn’t exist, they would have found other companies to do the work, but nevertheless, important contributions were made by Bell, Moog, and to a lesser extent, Carlton Controls and Cornell Aeronautical Laboratories. If their components failed, the mission would be lost.”

For those not alive a half century ago, it’s difficult to fully grasp what the event meant or how it united the world. A TV commentator at the time called it “the most audacious undertaking man has ever attempted.” Life would never be the same.

This year, on July 20 and 21, the Niagara Aerospace Museum is hosting events to commemorate the anniversary.

“We invite everyone to come to the museum and tell their stories, especially people who were involved or if their parents were involved,” said Don Erwin, a board member. “We want to highlight individuals who worked directly on the projects or had family members who did. We hope to record their stories.”

From Buffalo to Houston

Ordinary people from Western New York played important roles in the Apollo program, thanks to the significant contributions from Bell Aircraft. Most men from that era have either passed away or are now approaching 100 years old.

Paul Bardak of Tonawanda, and his sister, Judi Basinski of Amherst, have sharp memories of the 1960s leading up to the moon landing. When they were kids, their late father, Chet, worked for Bell as an instrumentation engineer, helping to develop the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, or LLTV.

In the summer of 1967, the Bardaks left their family home on Forbes Avenue in the Town of Tonawanda and moved to Houston so their father could work on the LLTV. The job was expected to last a year, and because they planned to return to Tonawanda, they retained ownership of their house but rented it out.

“I was (in Houston) for third and fourth grade,” said Bardak, now 59. “We were there for the two years prior to the mission, and my dad worked at the Johnson Space Center every day.”

Chet Bardak, who died in 2005, was born in Poland in 1928, emigrating to Buffalo as an infant. After graduating from Riverside High School, he attended college but left without a degree, according to his daughter. He took a job at Bell, where he remained for nearly 30 years. His wife, Julia, was a teacher in the Sweet Home School District. She died in 1996.

“I was in sixth grade when we moved,” said Basinski, now 63. “We knew it was going to be a temporary thing. It was a big deal because we had never moved before and were going so far away. We met a lot of people in Houston whose dads worked for NASA or were in some business connected to that.”

The LLTV was aptly named: the strange looking craft, resembling an oversized insect with spindly legs, flew like a jet pack, allowing astronauts to prepare and practice for their moon landing. Several vehicles were destroyed in the process.

“These were flying flight simulators designed to simulate the dynamics of landing on the moon in earth’s atmosphere,” Gordon explained. “There’s a very famous video of Neil Armstrong ejecting from one of them when it started to go out of control.”

Lunar gravity is one-sixth that of earth’s, so the challenge was to find a way to cancel out the remainder of earth’s pull.

“You can download a whole technical report online,” Gordon explained. “They used a jet engine gimbaled to the vertical axis within the center of the vehicle that was automatically controlled to cancel out five-sixths of the weight of the vehicle. Rocket engines controlled the rest. Every astronaut that was going to land on the moon flew it multiple times. Neil Armstrong went on record saying he wasn’t sure he could have successfully landed on the moon without that training.”

In the 1960s, however, the Bardak kids did not fully understand details of what their father did each day.

“We didn’t really know that much about the Apollo program,” Basinski said. “Dads back then didn’t talk much about work.”

Paul remembered attending open houses twice a year at the Space Center, where kids were allowed to examine lunar equipment being developed. It was a way to keep families interested, and for a kid it was fun to see the high-tech devices.

“It wasn’t until later when I recognized the significance of it,” Bardak admitted. “As Dad got older, we talked about it a little more. Whenever I tell friends now about what my dad did, they’re excited to know. I’m proud to mention him.”

Agena Engines

Experts agree that Western New York’s contributions to the space program were critical for success.

“If you recall John F. Kennedy’s speech (in 1961) that by the end of the decade we’ll land a man on the moon and return safely to earth, that returning safely to earth part began with Bell-designed engines,” Erwin said. “If that engine didn’t work, they didn’t come back. It had to be lightweight and reliable. Bell came through.”

The Lunar Module Ascent Engine, made in Niagara Falls, lifted the second stage of the module off the moon.

“At that point in the space program, rocket engines were still pretty embryonic,” Gordon explained. “Bell had developed a reputation for reliable engines with their Agena engine, which had first flown in 1958.”

The Agena engine had garnered respect after being installed in spy satellites a decade before.

“It was one of the most critical items in the entire Apollo stack because there was no backup,” Gordon noted. “Armstrong and (Buzz) Aldrin gather their rocks, come back inside, close the door and countdown five, four, three, two, one, and press the button to fire. If that engine doesn’t fire, they’re still there. If the descent engine failed when they were attempting to land on the moon, the ascent engine was their backup. Once they were on the surface, there was no backup. That engine had to work. And it was designed and built by engineers here in Western New York.”

As president of the Niagara Aerospace Museum, Gordon, 58, is an expert in aerospace history. He is also president of the Niagara Frontier Section of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA). With several colleagues from Moog, where he works, he presented a paper at the AIAA’s Sci-Tech conference earlier this year about Western New York’s contributions to the space program.

Erwin has a deep knowledge as well. A New Orleans native, he worked for NASA before relocating to Western New York with his wife in 2004. The following year, he wandered into the Niagara Aerospace Museum one weekend afternoon, hoping to entertain his kids. Soon he was volunteering to help develop the organization’s website, and currently serves as a board member.

“I’m an overall space nerd,” Erwin joked. “I’ve always been interested in it.”

Erwin was nine during the moon landing in 1969, yet his memories are vivid.

“Who doesn’t remember it if you’re old enough? Leading up to the mission, Walter Cronkite was on our black-and-white TV.”

In the days before online streaming or the ability to record video digitally, Erwin’s dad sensed the magnitude of the event. He took steps to commemorate it using cutting-edge technology for the time.

“My father taped the microphone from his reel-to-reel audio tape recorder to the TV and recorded all that,” Erwin said. “We still have those. When the astronauts stepped out onto the surface, we were all watching. It was amazing.”

The Historic Landing

The Apollo 11 mission, with astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin, and Michael Collins, touched down near the lunar equator on the lava plain named Mare Tranquillitatis, where they remained for more than 21 hours.

On Sunday, July 20, 1969, just before 11 p.m. EST, Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon. Declaring “That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” his words have passed into our cultural lexicon. (Grammar experts debate whether Armstrong misspoke. He should have said “That's one small step for a man…” Armstrong, who died in 2012, claims he added the “a,” but no one heard it. Transmission was grainy, however, so he may have said it, and years ago an audio expert suggested a blip in transmission may have caused the key word “a” to not be heard.)

Bruce Newman of West Seneca was about to turn 23 on that day in 1969, and planned to be married the following month. He remembers watching the black and white TV at his parents’ house in Greece, N.Y., outside of Rochester.

“Obviously, everybody was very excited. They landed in the afternoon, but announced they weren’t going to step onto the moon for another six hours. I was working at Bethlehem Steel in Buffalo, so I knew I had to drive back but didn’t want to miss it.”

Newman, now 72, became interested in space at a young age. In 1957, during the Sputnik era, an adult neighbor was part of Operation Moonwatch, timing the orbit of artificial satellites. In an era before digital tracking, Newman scanned the sky while his neighbor recorded times and locations.

Like so many, he was riveted by the moon landing in 1969.

“It was unifying,” he said. “This was before CNN, and networks were showing coverage in London, Singapore, all over the world. It was broadcast live in Times Square. There were some people who wondered why we were spending so much money to go to the moon when we had social problems in America, but once the rocket took off, everybody was all together in hoping we’d succeed.”

In addition to the moon landing, the list of Western New York companies contributing to the space program is impressive, according to experts. The former Cornell Aeronautical Lab — now Calspan — worked on flight dynamics. Moog developed hydraulic actuators that were used to steer the Saturn 5 rocket. Carlton Industry — now Cobham — developed air regulators for space suits that were used during the Apollo program. In Rochester, Eastman Kodak helped develop the optical system for the lunar orbital satellite that was used in 1966 and 67, which took photos of the moon to help determine where astronauts should land.

“There is a lot of Western New York blood, sweat, and tears that went into the whole program,” Erwin said.

Gordon recalled Apollo 16, which landed on the moon in 1972, and was led by Commander John Young. After touching down successfully, the crew ran a series of required checklists to ensure their equipment was working properly.

“About a minute after landing on the moon, the first thing Young said that wasn’t scripted was ‘Flew just like the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle. Piece of cake,’” Gordon said. “What a tribute to Bell and Niagara Falls ingenuity.”

And another moon story...

Because the moon landing was so risky, insurance companies would not offer coverage for the astronauts in 1969. So Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins participated in a novel way to ensure their families were financially secure if something went wrong.

Prior to the launch, while in quarantine, they signed specially designed envelopes with the Apollo 11 logo, called covers. These were given to a friend and then mailed home to their families, so that the postmark included key dates, such as July 16, 1969 (the day of the launch) and July 20, 1969 (the day of the moonwalk). If the astronauts did not return, their loved ones could auction off the covers to raise money to support surviving relatives.

It is estimated that only 1,000 covers were signed. Those covers are now collectors’ items, and Buffalo Tales photographer Steve Desmond owns three of them.

“Growing up, my goal in life was to win the highest honor in the Western New York Science Congress,” Desmond said, explaining his interest in space. “I picked up a camera in 1980 to take photos of the moon and stars through a telescope.”

(Desmond did win the award; his photo of the moon appears above. Soon, photography became his passion.)

Using a reliable collectibles dealer with access to the covers owned by Aldrin’s ex-wife, Desmond purchased them in 2003. While he paid two and three thousand dollars for each, experts now appraise them around $30,000 each. Desmond keeps them stored in a safe deposit box.

© 2019 by Jeff Schober

The public is invited to the Niagara Aerospace Museum's "Apollo Party and Open House" on the weekend of July 20 and 21. For complete information, click here.

__________________________________________________________________________________

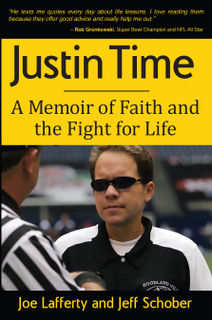

Looking for an inspiring book? Read Jeff's latest release: Justin Time: A Memoir of Faith and the Fight for Life, co-authored with Joe Lafferty. Click the cover for more information.

Comments